Confronting the Demon Change

Uncentered beings experience anxiety or dread that prevents them from accepting change. If we fail to undergo spiritual annealing, our enemies will take advantage of our fears and imbalances.

The affairs of the world will go on forever. —Milarepa

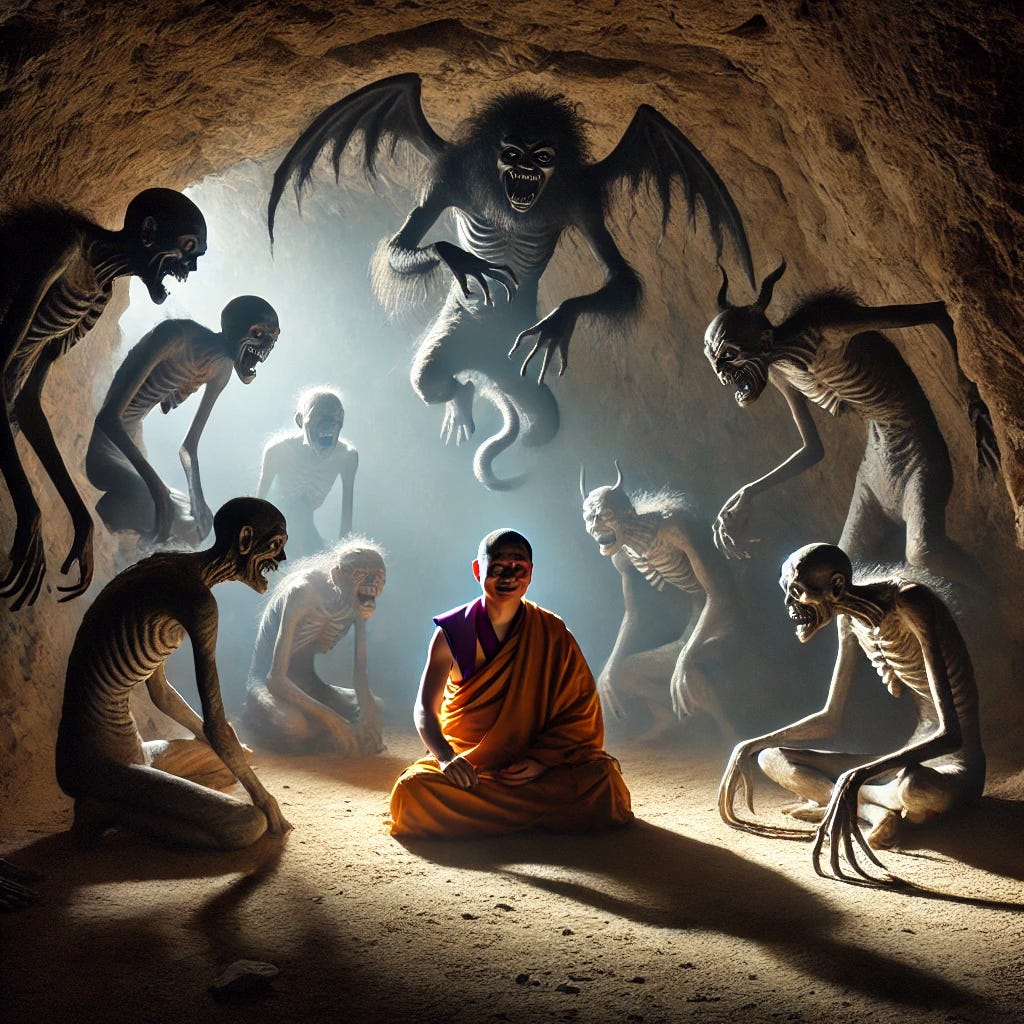

Milarepa, one of Tibet’s most beloved teachers, faced a powerful set of entities during his solitary meditation in a cave. According to lore, Milarepa encountered terrifying demons that embodied his fears, doubts, and unexamined assumptions. At first, Milarepa tried to cast the demons out, but they persisted in haunting him.

Rather than fleeing, he welcomed each demon, inviting them all to stay to teach him.

One of those demons is called Change.

Confrontation is the jarring, sometimes traumatic process of facing existential reality and integrating that reality while remaining centered. Centeredness, or equipoise, is an internal balance that positions one to reflect and take wise action—a state in which the head, heart, and gut are aligned.

Confrontation without centeredness is dangerous. Uncenteredness can invite anxiety and existential dread. If you are to reckon with the brutal reality of change, you will first need to find equipoise.

As I wrote in a past codicil,

Confrontation captures both the conflict and the potential for revelation that arises from exploring certain shadow truths head-on.

There are at least two major types of confrontation:

The first deals with the existential inner. Though themes such as death, change, and evil are connected to some mind-independent reality, the process begins with our subjective and intersubjective integration with that reality.

Confront the existential inner first.

The second deals with the existential outer. Though certain societal circumstances or social facts are rooted in some mind-independent reality, most people go about in a kind of collective denial, either as digital zombies or timid herd animals.

Confrontation of this sort dispels such denial and simply wakes people up to a reality they might not have been able to perceive in the past. It can involve reports such as I feel like I developed a lens, an antenna, or another sense. Or, Once I saw it, I saw it everywhere.

Complete confrontation, within and without, can mean a profound reconfiguration of one’s identity—a rebirth that includes philosophical, psychospiritual, and cultural dimensions. Confrontation opens one to transformation and is itself transformational.

Yet, we change, and the world changes moment by moment, making everything seem out of our control.

The Sage’s River

The old hermit sage Heraclitus famously declared that everything is in motion. Nothing remains fixed. "You cannot step into the same river twice," he is said to have written. This image captures impermanence as an essential feature of one’s identity (you) and the world (river), emphasizing that everything is in constant flux. The water, the currents, and even the observer become different entities in each successive moment.

The river image connects to Heraclitus’s unity of opposites conception, auguring dialectics. Though ever-changing, the river remains identifiable as such. Stability and instability coexist in mutual definition, demonstrating how apparent opposites intertwine, as do day and night, life and death, creation and destruction.

The old sage’s work is an intellectual trailhead for confrontation, which is ultimately an emotional and spiritual endeavor. Heraclitus invites us to acknowledge the dynamic nature of reality and asks us to dispel any illusions of permanence. Once dispelled, we reveal the beauty and complexity of a world that unfolds ceaselessly. To the old sage, the demon Change is not so much a set of continuous disruptions as the forces of the All aspiring to balance and harmony.

Deepening Confrontation

In more quotidian terms:

Things happen and never stop happening.

Change always entails loss.

Change can be purposeless.

The direction of change can be uncertain.

The past can never be reclaimed.

Your identity is neither fixed nor unitary.

Nothing is stable.

Some day, everything will end for you, yet everything will keep changing.

Both life and history are a series of processes and events.

A process is a continuous pattern sequence that shapes our reality over time. This shaping is not static or linear but dynamic and cyclical. History, culture, and civilization require continuous motion, recognizable patterns, and repetition.

An event, on the other hand, is a great disruptive pivot within a process. At this inflection point, accumulated forces of change come to a head and cause a significant shift in an individual’s life or the trajectory of history.

Hierophants Bard and Söderqvist write that an event is a “spectacular occurrence,” or more distinctly, an occurrence “with spectacular consequences for a certain phenomenon or specific region of the universe.”

Before confrontation, one can experience denial and imagine static form, fixedness, and foundational axioms on which to build our knowledge. During confrontation, one can experience dread and a total loss of control. After confrontation, one can experience a paradoxical sense that control is restored—but not due to the fixedness of things. Instead, one resigns to the fact that change is unceasing but sees that she can become a catalyst and conduit for flow.

But can there be too much change?

Anxiety and the Delta

Let’s accept that change involves cyclical processes and punctuated events. Now assume there is a natural range—a manageable rate at which events occurred to our forebears on the ancient steppe amid processes such as sunrises and seasons. A herd of mammoths has trampled their camp, or a flood has sent them scurrying to high ground.

Our ancestors had to adapt.

A natural range was established long before settled agriculture or the agora. Contemporary society, with its rapid advances, diverse milieus, and morphing cultures, accelerates the event rate beyond the natural range.

Experiencing too many events in time induces anxiety.

The event rate will continue to accelerate until the cycle of endings collapses a civilization. Such acceleration will continue to induce anxiety until the fall. Humans persist in a state to which our ancient amygdalas are not quite suited. Happily, we evolved inner executives to override excessive neurological omens.

Even in conditions of upheaval, you can confront change and expand your sovereignty. Self-control arrests anxiety. First, find centeredness, restoring any internal locus of control. Then, select and specialize. That is, do what you do best and trade for the rest. Finally, exit relationships and systems that cause imbalance or restrict you from expanding your sovereignty, where expanded means becoming more robust and resilient.

We can confront change and then learn to adopt new protocols, making it more likely that one will return to the natural range. In an important respect, this means learning to filter events. Some spectacular occurrences will be imposed on you, and you will have no choice but to submit. You might invite other events into Milarepa’s cave, but you will not let these transform you utterly. In equipoise, it is possible to compartmentalize events, even in waves like the plagues upon Pharaoh.

Between Primitivism and the Machine

We change our technology, and our technology changes us. As technology intermediates, it eats up more of our lives, becoming like an evolving superorganism. Hyperreality encroaches. Maps cover maps that cover territories. The accelerating development of this superorganism pushes many to retreat. Some embrace primitivism and imagine a return to an Eden that never was. Others go to the other extreme, seeking to replace our roots with wires, that is, of augmented selves and societies.

But we must stay rooted, lest we become lost in Baudrillard’s precession of simulacra.

In striking the right balance, we fulfill our destiny to create. And in creating, we escape the primitive. Such is the Promethean promise. There is no turning back. Yet, we must stay rooted in our natures. For if we cut away those roots, we will become unmoored. Unrecognizable. Wholly other. At that point, we will cease to be human. We are like the flora and fungi connected by the mycelium. Shorn of our roots, we are no longer connected within the same human community.

Rooted or not, though, change is constant.

Coda

Milarepa’s story exemplifies both inner and outer confrontation. It calls for courage, presence, and surrender to what we cannot control. It challenges us to be psychospiritually prepared for unexpected teachings, preparing us to be catalysts and conduits of flow.

Confrontation is not for everyone. Uncentered beings will experience anxiety or dread that prevents them from finding some measure of peace and an inner locus of control.

But if too many of us fail to undergo this spiritual annealing before our enemies strike, they will surely exploit our imbalances, fears, and unconfronted demons.

The Law of Flow is Everywhere

In the Amazon basin, far below the rainforest canopy, a network of roots stabilizes a thick trunk. Mirroring the branches and twigs among the leaves above, the roots below split into smaller roots, which split into yet smaller roots, extending outward to absorb water. All that water gets stored in the tree's cells.

"Rather than fleeing, he welcomed each demon, inviting them all to stay to teach him."

...Examining and learning from our fears instead of avoiding the sources of them... what a powerful way to turn the tables on them. Thank you for this piece of wisdom...