Who Are You?

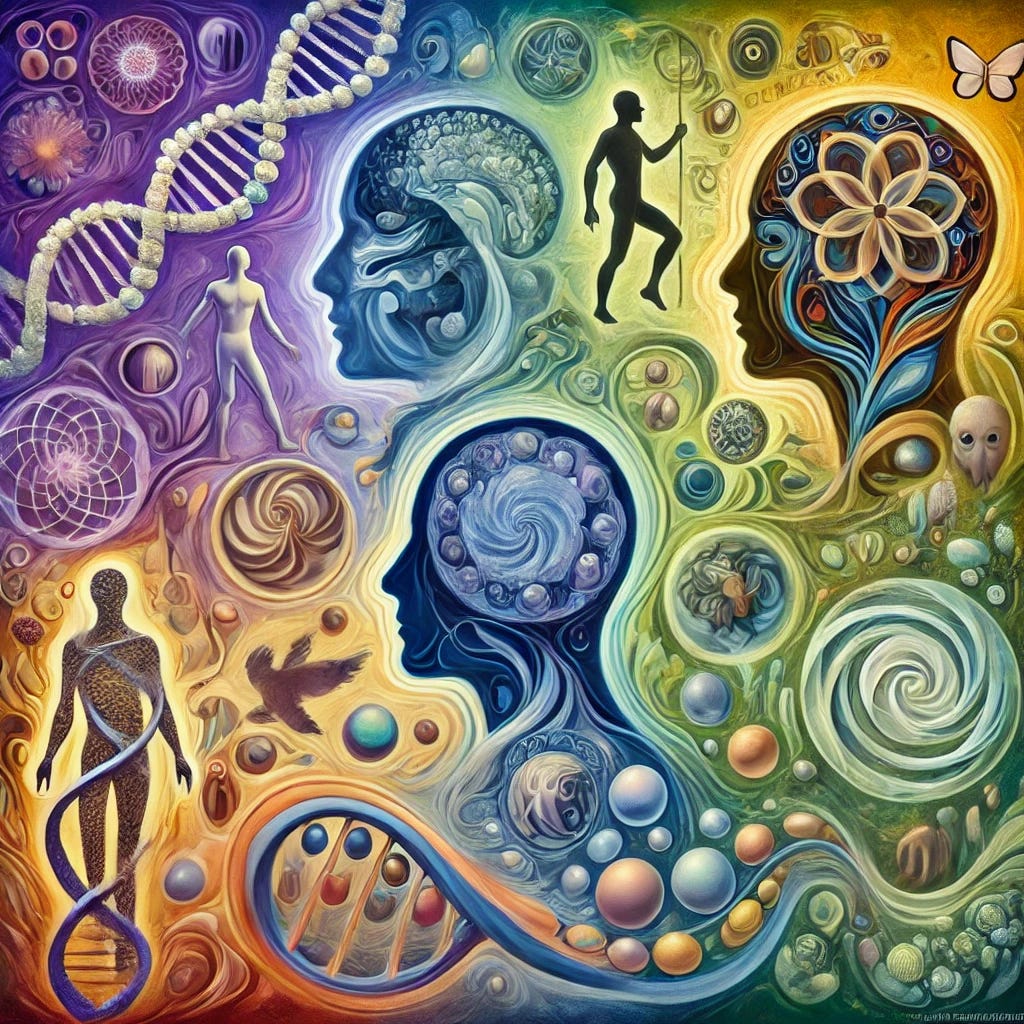

Integrating competing models of the self as a basis for expanding radiative self-sovereignty.

In the Empire of the Mind symposium, we will confront the existential realities of change, evil, and death. But in constructing an Empire of the Mind, why begin with change?

As our world transforms, we must adapt and improve.

We must, therefore, shake our attachments to comfortable and convenient conceptions of who we are. And that requires deconstructing and reintegrating the very idea of Self. Only then can we rebuild our self-conceptions in self-sovereignty.

Self: The Rudimentary Conceptions

Our understanding of self emerges from four fundamental frameworks:

The Evolved Brain-Body (Charles Darwin) represents the naturalistic view, where human identity emerges from evolutionary processes through natural and sexual selection. This perspective sees our core nature as relatively fixed, with personal identity largely emerging from biological inheritance.

The Generalized Other (George H. Mead) offers a social constructivist view, emphasizing how we develop through internalizing collective attitudes and social norms. Our sense of self forms and evolves through continuous social interactions and our interpretations of how others perceive us.

The Buddhist No-Self (Gautam Buddha) transcends the nature-nurture dichotomy, revealing our fundamental interconnectedness with all existence. This nondual perspective suggests that attachment to a fixed personal identity creates suffering while recognizing our interdependent nature leads to liberation.

The Vascular Identity (Derek Parfit) presents a dynamic view of selfhood as a continuous flow of experiences and mental states rather than a fixed entity. This framework emphasizes psychological continuity over rigid self-identity, acknowledging both change and connection in our ongoing experience of self.

These perspectives range from materialist (Darwin) to social (Mead), transcendent (Buddha), and processual (Parfit), offering complementary insights into the nature of human identity and consciousness.

Complementary?

It would seem that these are contradictory. Surely, only one conception is correct. But imagine each conception picks out properties of a greater understanding that, though elusive, rewards serious contemplation. Once we can appreciate these properties, we can revise our understanding of ourselves and establish change modalities that are more responsive to introspection and agency.

The Integration Matrix

Let’s take these four rudimentary conceptions and organize them into an integration matrix. 1 and 2 compose the x-axis. 3 and 4 compose the y-axis.

Let’s explore this new matrix one quadrant at a time.

1. The Rooted Tree of Selves:

Biological Contiguous Relational Identity

Imagine identity as a living, breathing extension of our biological roots, continually shaped by evolution. At its foundation, our sense of self is deeply intertwined with inherited traits and survival instincts. This approach begins with the “grain” of biological development—our DNA, genetic code, and shared history as a species. But unlike a static blueprint, identity here is flexible. It’s a flowing, branching process that remains continuous even as it transforms, constantly adapting within flexible bounds set by our biological natures.

This relational approach to identity sees us not as isolated entities but as branches on a broader “tree of life.” We are inextricably connected through a shared biological heritage. Therefore, our sense of self is not purely individual but relational. We form our identities in the interplay with others, each contributing a unique piece of a vast and interconnected evolutionary story. In this view, a sense of moral responsibility arises from these overlapping connections—an understanding that we share an origin and biological overlap. Ethical considerations extend from the recognition that our actions reverberate through this relational web, influencing the lives of others and the natural world around us. Such is not to commit the naturalistic fallacy but to offer reasons why humans contrive ethics, acknowledging inborn dispositions.

2. The Tree of Other Voices:

Socially Constructed Relational Identity

While biology provides one frame, another layer shapes us: social interactions and cultural contexts. This view positions identity as socially constructed, fluid, and responsive to the people and narratives around us. Each of us crafts our identities through our roles and relationships, drawing from a collection of perspectives, a concept akin to what sociologist George Herbert Mead called the “Generalized Other.” Our sense of self is continuously reshaped by the expectations, values, and norms we absorb from those around us.

In this social constructivist view, identity is always in flux as a collection of selves, connected and continuous through time. These selves mirror the shifting landscapes of social networks, and our identities develop alongside those of our communities and societies. Relationships become the canvas on which our sense of self is painted, and individual autonomy is shaped and constrained by this vast social matrix. From this perspective, responsibility is not so much about individual choice as navigating and responding to the interconnected, evolving social contexts in which we find ourselves.

3. The Rooted Buddhist:

Bio-Substrate with No Fixed Identity

Taking a different angle, the third framework confronts identity as impermanent, an illusion arising from biological processes without a fixed essence. Here, identity is seen less as an intrinsic self and more as an epiphenomenon, a temporary projection created by the evolved brain and body. Evolution has led us to a place where behavior and thought patterns emerge from biology, yet there is no underlying, enduring “self” behind these patterns. Instead, evolution requires we live in that illusion. What we consider our identity is simply a biological process playing out moment by moment.

This perspective, informed by Buddhist thought and evolutionary neuroscience, suggests that clinging to the illusion of a fixed identity brings suffering. By recognizing our shared impermanence and embracing the notion of “no-self,” we liberate ourselves from the illusion and barriers that prevent us from cultivating compassion and non-attachment. Under this view, ethical behavior flows from an understanding that all beings’ lives are transient. Compassion becomes not just an ideal but a natural response to this recognition. We come to see ourselves—or illusory selves—in others, united within our shared, fleeting nature.

4. The Nondual Other:

Socially Constructed Impermanence

Finally, we arrive at a perspective that combines the social and the impermanent, viewing identity as a series of roles we adopt temporarily, without any essential core. Here, identity becomes a form of social performance shaped by cultural expectations and contextual roles. Like actors on a stage, we play multiple roles, each influenced by the situation and the audience, with no single role defining our “true” selves.

In embracing impermanence within the social construct, this framework suggests a non-attachment to any one role. Social identities are acknowledged as temporary, allowing for freedom of movement between different expressions of the illusion. The focus shifts from personal autonomy to collective interdependence, where connections are made through shared experience and mutual understanding. Ethics in this context arise from mindful engagement with others’ ephemeral roles, grounded in the knowledge that such roles—and the identities that come with them—are always shifting.

Which Quadrant?

The foundationalist will be tempted to ask: Which quadrant most closely represents reality? But identity, as such, is a collection of all such perspectives without a foundation. Instead, we respect the lessons of each quadrant as we grant it emphasis. For example, we must acknowledge biological constraints even as we admit that others shape us through our interactions with them. We can accept, without contradiction, that in one respect, the idea of a fixed self is an illusion, even as, in the other, we grant that the continuity between these pluriself illusions offers something on which to hang justifications for dignity, morality, and personhood.

Most importantly, for our purposes, engaging this important matrix as an integrative whole allows us to see change modalities. That is, we can better identify the vectors of (and limits to) our personal transformation. And your transformation will happen. The only question is whether that transformation will be passive or active.

In other words, will it happen to you, or will you happen to it?